Now more than ever, we need to bring back Browserchoice.eu

Jordan Maris, March 10, 2021

In March 2010, following a complaint from the European Commission, Microsoft launched browserchoice.eu. This application and website was a response to accusations that Microsoft had abused its dominant market position by bundling its Internet Explorer browser with its Windows operating system.

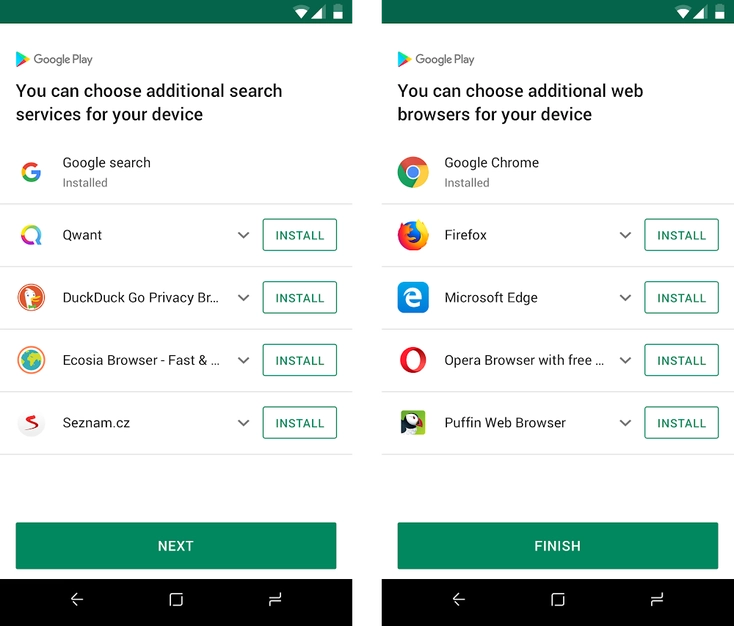

The application, which was automatically presented to all users in the European Union, informed consumers about the various browsers that were available and gave them the option to download alternatives to Internet Explorer. For many users, it was a chance to discover the existence of alternatives that they may not have been aware of, maximising user choice and creating a level playing field for competition.

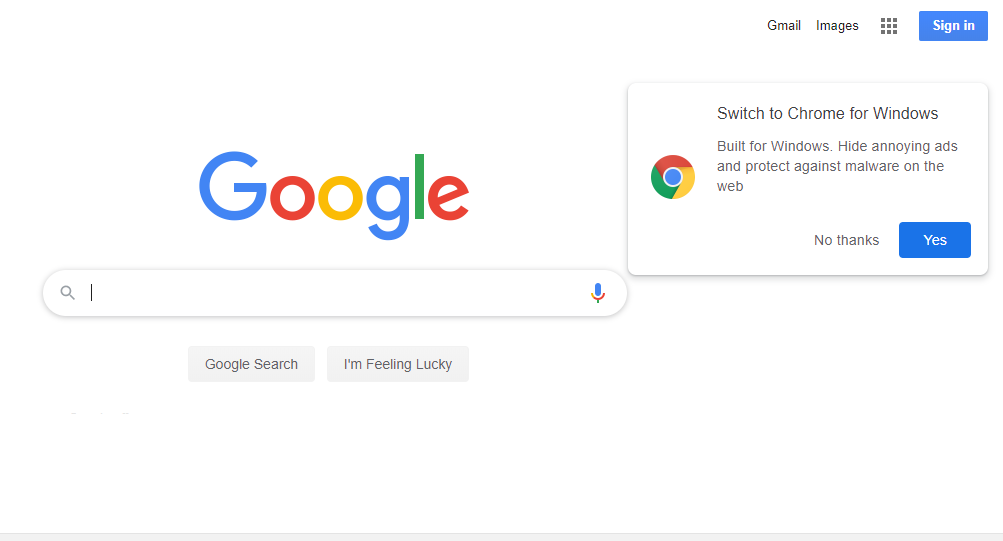

The obligation to display the Browserchoice page to Windows users came to an end in 2014, and Microsoft pulled it quietly and without ceremony. Although innovative, in its lifetime, the application was not as successful as expected, the massive expansion of Google Chrome is more easily attributable to Google advertising it on the homepage of the worlds most used search engine than it is to browserchoice.eu. Why then, do we need to bring it back?

Edging on unreasonable: Microsoft’s campaign to force their browser on Windows users.

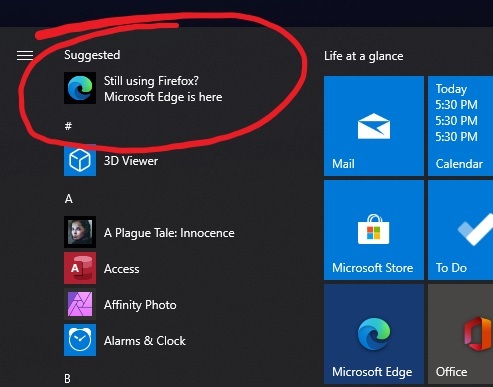

Firstly, Since the demise of BrowserChoice.eu, Microsoft has began aggressively pushing it’s Edge browser on consumers. The Edge browser was delivered to customers without their consent via Windows Update, immediately launches itself on boot, pins itself to the taskbar, and tries to force the user to switch. Furthermore, it clears the Windows “Default Browser” setting and tries to get the user to change that setting to Microsoft Edge.

Finally, Microsoft has integrated pro-edge advertising throughout their operating system, with adverts appearing in the start menu and in default application dialogs, advertising Edge as the “Recommended Browser”. Attempts to search for alternative browsers using Microsoft’s Bing search engine also display large banners urging users to install Edge, with links to the alternative browsers only further down the page.

Just this year, Microsoft took another step towards preventing the user from changing the browser, by making the user individually change the default app for every possible type of link used in the browser.

Blink and you’ll miss it: the rise of Chrome and Blink

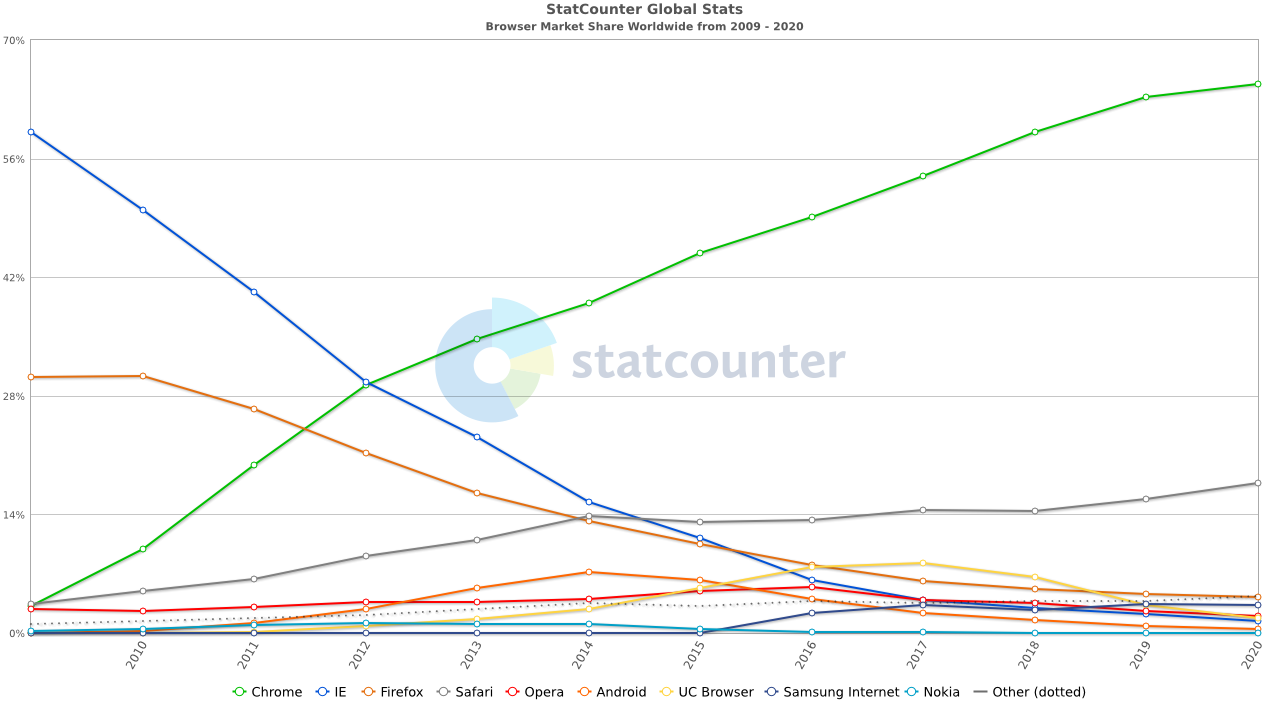

In the early days of browserchoice.eu, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer browser commanded a 55% market share on the desktop, with its nearest competitor, Firefox, at 30%. Today, all these browsers are dwarfed by Google Chrome, which holds a 67% market share.

This dominance is an issue both for the web itself, but also for the user: Google have made use of Chrome’s dominant position to gather more data on users, as well as to strengthen its dominance of the online advertising space. Firstly, Google recently implemented an update which automatically ties the browser to a Google account as soon as users log in to any Google service and without the users consent, subsequently sharing their history with Google.

Secondly, Google recently promised to phase out 3rd party tracking cookies from Chrome, which, up until now, has been a cornerstone of their business as an advertising company. This promise, however, is not the altruistic act of kindness it appears to be: in reality, Google’s replacement FLoC not only continues to infringe on users privacy, but potentially breaks the GDPR, and gives Google de facto role of gatekeeper of the online advertising business.

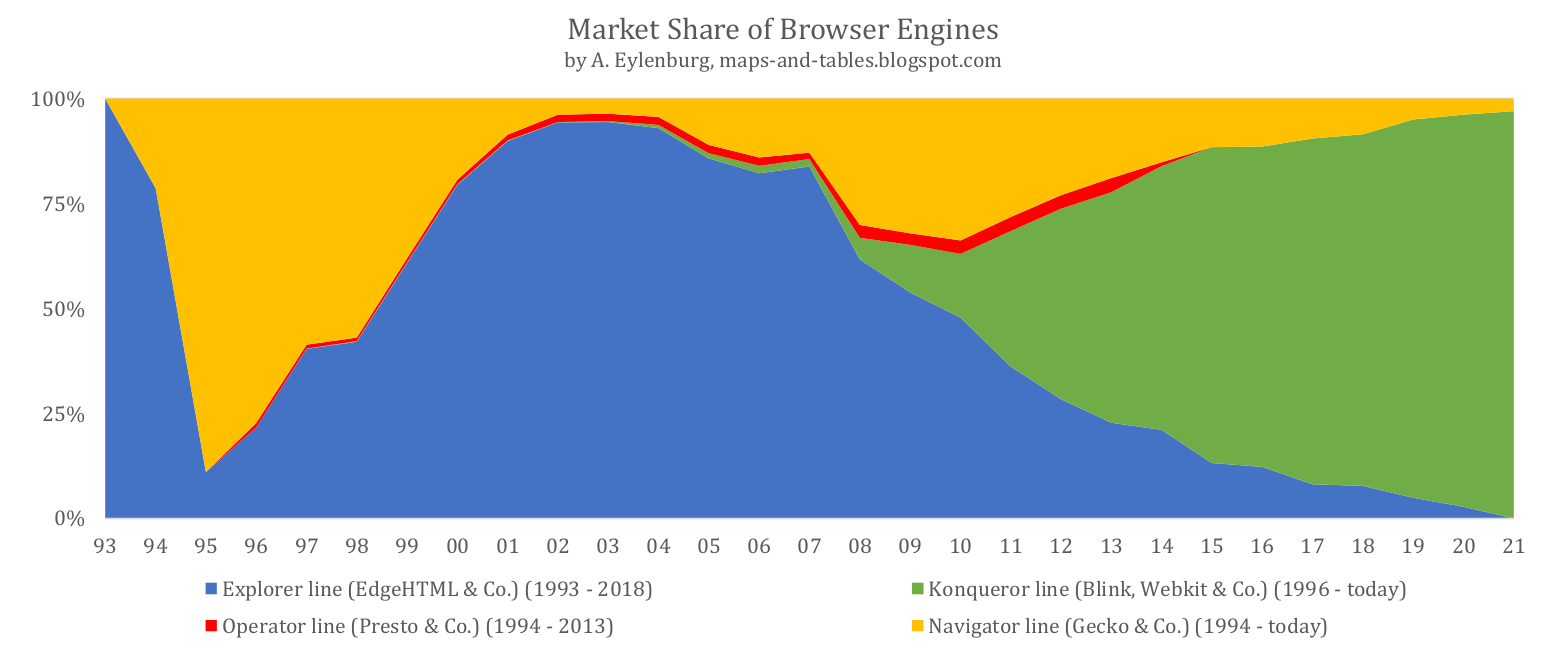

But the greater threat comes from the growing dominance of the Blink Engine in the browser market. Blink is the “engine” behind the Chrome Browser, it is developed primarily by Google themselves and is open source, meaning that the code can be used for free by other organisations. The engine of a browser is what allows it to display webpages.

In 2010, when browserchoice.eu was launched, a wide range of Browser Engines were under development: Webkit was the engine of choice for Apple’s Safari, while Microsoft’s Internet Explorer used Trident, Mozilla’s Firefox used Gekko, Opera used Presto, Edge used EdgeHTML and Chrome used Blink. Today, only Safari and Firefox have retained their unique engines (Safari continues to use Webkit and Firefox uses Gecko), while all other browsers have switched to Blink. A massive 82.3% of Internet users now use browser based on Blink, and this is a massive danger for the open web, as Popular Mechanics points out in their article on the dominance of Blink.

Up until now, healthy competition in the market for browser engines has meant that no single organisation dictates the standards that the web operates on. Working groups such as the w3c and whatwg, consisting of all major players in the Browser market discuss and set standards. While this system was seriously dysfunctional, it prevented any one party from gaining total control over the way the web is displayed. Now it appears that the system is at risk of collapse: as the market share of Blink has grown, Google have become more and more comfortable with implementing changes directly without working with existing working groups.

This, for example, was the case with the new FLoC advertising system, which Google implemented without discussion and are now testing in the Americas much to the concern of many inside and outside the w3c. It can also be seen with their SPDY protocol, or ShadowDom v0, all of which slowed performance of Google services in browsers other than Blink-based ones.

Conclusion

It is unlikely that the reintroduction of browserchoice.eu would be justifiable under EU competition law. Since the vast majority of users are no longer using the default browser, some would argue that users know about the options available and can weigh-up the pros and cons and make an informed decision. That is not what we are seeing today.

What we see today is Gatekeepers using their incredible influence to push their products, while leaving other market actors with little to no visibility, even actively taking actions to damage competitors. Microsoft did it by pushing Edge on Windows while trying to block out competitors, and Google did it by pushing Chrome via its Search Engine all while making changes to the architecture of the web which negatively affect performance of other browsers.

The upcoming Digital Services act package (DSA/DMA) should help remedy some of these issues, and we have already seen action from the Commission forcing Google to propose alternative browsers to mobile users on Android, although no such progress has been made on iOS, where only Apple’s browser engine is allowed.

If we do not want a web dominated by a handful of companies, the DMA must take action that goes beyond the basis of competition law. Bringing back browserchoice would create a level playing field for competition, and empower consumers to make an informed decision about the most important application on their devices, fostering healthy competition that will make the web better for everyone.