Get onboard: there has never been a better time to fix France's transit.

Jordan Maris, November 20, 2021

France’s regional transit suffers from poor ridership, terrible performance, and frequent delays and closures. Considerable investment and change is needed to fix it, but luckily there has never been a better time to do so.

The Climate Crisis

It’s getting hot in here, we are to blame, the consequences will be disastrous, and we are not doing enough to stop them: that is the jist of the IPCC’s recent 4000 page report on climate change. The report will be the first in many that will further push governments to act to address the causes of climate change.

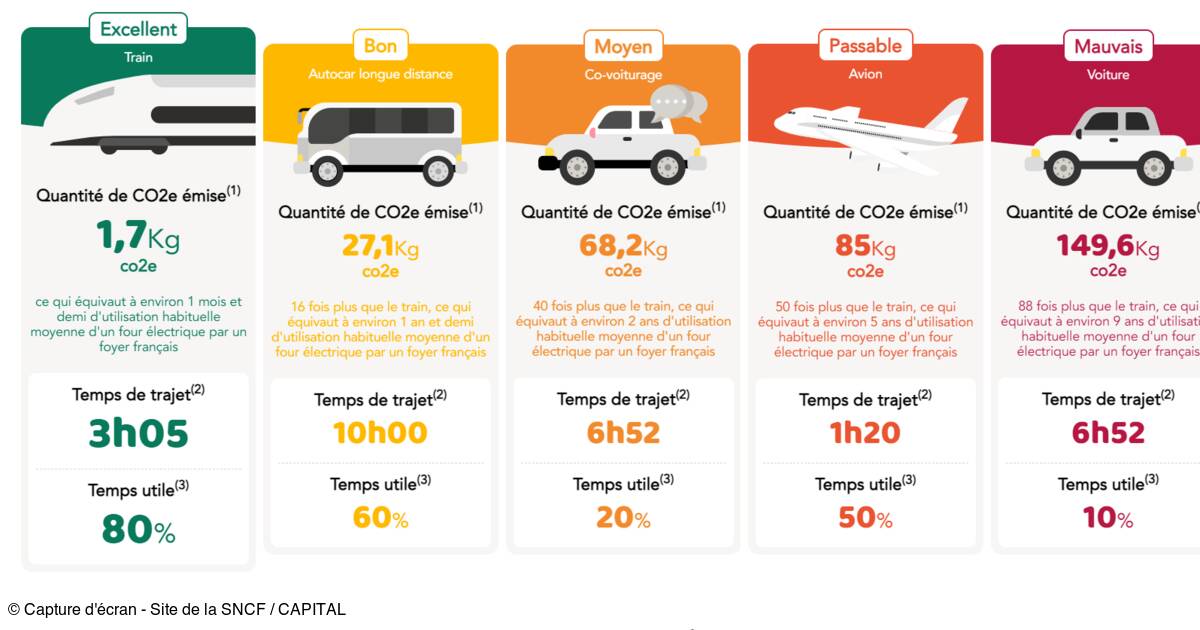

Transport (23.5%), Shipping (3%) and Aviation (3%) make up about 30% of Europe’s emissions, and offer significant room for CO2 reductions. Some argue the advent of the electric car mean that a focus on rail is not particularly necessary. However they often forget the additional demand for electricity created by electric vehicles, which is looking more and more difficult to meet, especially considering the lack of political will to build more nuclear power, and the lack of clean alternatives that provide both the stability and the volumes of power needed to bridge the gap.

Since the cost of energy and CO2 costs per person per kilometre are significantly lower in rail when compared to other means of transport, it is vital we get people and goods out of planes, cars and lorries and on to trains if we wish to reduce our emissions and still have enough power to keep the lights on.

These goals are at the heart of the EU’s Green deal, Year of rail, and the pandemic recovery plan. Hence there should already be significant political momentum behind this change. At present, France has allocated about €5bn to rail as part of its recovery package, and while a one-time investment simply isn’t sufficient to address the networks’ issues, it is a good start.

Independently of political will there is also a massive social movement to address the causes of climate change: people, especially young people, are willing to abandon their cars in favour of rail. Though climate change isn’t the only reason young people are abandoning cars.

A changing society

The car as a burden

To the generations that came before mine, the car was a symbol of individual liberty: the freedom to go wherever you want, whenever you want. For my generation, that has changed: the high cost of fuel, insurance and Services, as well as parking mean that for many the car has become more a burden than a liberation.

This is reflected in the steadily decreasing number of young people who are passing their driving licences, and while public transport and cycling within cities are often a sufficient substitute to the car, getting around outside of cities is still a major challenge.

Should the current trend continue, less and less people will want to drive, which leaves a significant opening for public transport to fill the gap.

But young people aren’t the only ones: more and more cities in France are also shunning the automobile, reversing a sixty-year old policy of putting the car first, reducing speed limits, adding traffic-calming, and replacing or reducing car-infrastructure in favour of public transport, green space, cycling and pedestrians.

The reasons for this are numerous: reducing air and noise pollution, as well as injury and mortality due to car accidents and traffic are some of the commonly cited social reasons, but there is also a significant economic argument: space allocated to cars simply isn’t economically productive, and incurs a significant maintenance cost. We saw examples of this at the beginning of the pandemic, when many roads were closed for on-street dining, and in many cities these roads have remained closed since then.

Commuting by car from the suburbs or surrounding rural areas to cities will hence become less and less attractive, which is why it is vital that authorities offer a practical alternative to people who live outside of cities. Especially considering their number may be about to grow significantly.

The Pandemic, teleworking, and the beginning of an urban exodus?

The pandemic irreversibly changed work, challenging the long standing paradigm that people need to be in the same building and under close surveillance to be productive. For over a year, teleworking became the norm for a great number of people, and it worked: many were as productive, if not more so when working from home. As a result, a great number of companies have significantly widened teleworking possibilities for their employees.

This, coupled with the experience of being “cooped up” during the pandemic, and increasing housing and rent prices, could fuel a rural exodus, with many people - especially families - moving out of towns and cities. This is not a negative thing: it has the potential to bring down the cost of housing in cities, and give rural economies a vital boost, in a time when many of them are in decline.

But there remains a missing piece to the puzzle if this rural exodus is to come to pass: teleworking has its limits, and getting both to your place of work, to shops, leisure and other services currently requires a car in most rural areas. Giving people an attractive, reliable and inexpensive alternative to driving is hence vital if we want such a revolution to come to pass.

New technologies

While the current social, environmental and economic context is at the heart of why now is the best time to fix France’s trains, there are also a number technological innovations which open up new possibilities for novel transport solutions.

A new source of energy: Hybrids, Hydrogen and Batteries

Part of the effort to address Climate Change will be encouraging people to switch from driving to rail, preferably driven by green energy.

However, at present only 55% of France’s rail network is electrified, and while many lines can and should be electrified, it is important that the money we invest be used to provide the largest possible benefit, hence it is difficult to justify electrifying rural lines with low overall traffic, at least for now. The Diesel trains which currently run on these lines are considerably more climate-friendly (per-passenger) than driving, but they still emit CO2 and pollute the air. They also present a number of other issues: low efficiency (around 46%), high maintenance costs due to a greater number of moving parts, and unstable fuel costs due to the use of fossil fuels.

Using Hybrid trains, which can take energy from overhead wires and on battery or hydrogen fuel cell can significantly reduce fuel costs and emissions, especially on lines that are partially electrified.

For longer distance trains on unelectrified lines, the use of hydrogen fuel cells may be a better choice than batteries, and while Hydrogen is currently in its infancy, and is relatively inefficient compared to battery or electrified rail, German rail operators using the technology are reporting similar costs to Diesel. The development of higher capacity batteries also offers an alternative to overhead electrification with extremely high efficiencies and low maintenance costs.

Autonomous rail and ultra-light rail

Coupled with these innovations in power are innovations in rolling stock and operating technology. These innovations are also susceptible to drive down operating costs.

Autonomous rail

Autonomous Rail has been in development in France since 2016, and testing in open environments began in 2021. In the future, autonomous rail could mean trains can be operated without drivers, or from a central command post requiring less people.

It is vital to remember that such technolgoies are still experimental, and that any deployments in the coming years are likely to focus on isolated lines with low complexity, where they are not likely to come into contact with trains driven by humans.

Hence, the primary use-case of such technology would be branch and rural lines, where they could significantly lower operating costs, making these lines economically and politically viable, especially when combined the innovative power solutions described in the previous section.

Ultra-light rail

Having emerged in the past couple of years, ultra light rail remains for the most part, a conceptual form of transportation. The idea being to make use of the light materials to build tramway size vehicles that have a much lighter overall weight than traditional trains.

Concepts, such as Navette Ferroviaire and Taxirail are designed for branch lines with low ridership, operate using hydrogen or onboard batteries. They have lower capacities and speeds when compared to traditional rail, but operate autonomously, at lower cost, and could significantly reduce wear on rail infrastructure, and claim they can even operate on poorly maintained infrastructure. Some proposals even allow for on-demand transport.

This could be significantly reduce cost of operation, and make the operation of extremely rural railways more financially viable. Such a combination was recently proposed as part of the “navette ferroviaire” project in the Creuse, France.

New construction materials

Another innovation is the development of more advanced construction materials.

For hundreds of years, most of our railways used wooden sleepers, frequently treated with a variety of unpleasant chemicals to extend their lifespan (12-15 years total). Wooden sleepers have the advantage of a low production cost, moderate weight, and excellent vibration-damping properties. However, as trains have got faster, and as the consequences of the use of the aforementioned chemicals came to light, the industry began to experiment with other solutions.

First developed in the early 50s, Concrete sleepers are significantly more expensive to buy, and heavier and harder to lay compared to wood, but they have a longer life-span (40 years), and require less maintenance, provide better stability and do not suffer some of the issues wooden sleepers suffer (fire risk or bug infestation). As a result, they can contribute to reducing operating costs in the long term.

While wooden sleepers still remain in service on numerous lines in France, they are slowly being replaced by concrete, but as this replacement takes place, a third alternative has presented itself.

Plastic composite railway sleepers

Made from 80% recycled materials, Plastic Composite railway sleepers represent the best of both worlds: light, and cheap to lay like wood, with decent vibration dampening and elasticity, but with a much longer lifespan and low carbon emissions.

These sleepers do, however, have some issues: they are more expensive than wood, do not exhibit the same strength as concrete and their theoretical operating lifetime remains to be proved.

As these technologies develop further, they have the potential to bring down the costs of installation and maintenance of rail over a long period, and hence reduce the cost of rail tolls.

Addressing the “last mile” problem

Finally, in France a vast number of train stations, especially in rural areas, are quite far from the centre of the towns or villages they serve. One key issue, and factor that dissuades people from using public transport, is that they still have to drive to the station.

New technologies, such as eBikes or autonomous vehicles have began to emerge, in a way that may help address the so called “last mile” problem. In the future, we can imagine that small autonomous vehicles could run between population centres and train stations at minimal cost and with low maintenance, ferrying passengers to the train station either on a schedule or on demand.

Conclusion

The social and environmental context we live in shows there is a greater need than ever for improvement to regional rail networks. Building a system that better serves people will involve expanding service, and reducing costs. Luckily, new technologies have the potential to do just that.

Despite this, significant barriers still exist, in the next article, we will discuss the flaws in French regional rail as it stands, covering the infrastructure itself, the flaws in policy which have resulted in closures and slow-downs, the consequences of those closures, as well as the issues with the passenger experience, service design and planning, and subscriptions and governance.

This Article is the second of a series on fixing France’s regional trains. You can find out more in the introductory article, here.