What's wrong with France's transit infrastructure?

Jordan Maris, April 06, 2022

The greatest weakness of the French rail sector is the lack of a planned, long term vision for its rail network. The first step towards improving regional rail in France is acknowledging that we want to improve the network, not just maintain it, deciding on priorities for projects, and allocating sufficient funds to maintain the network.

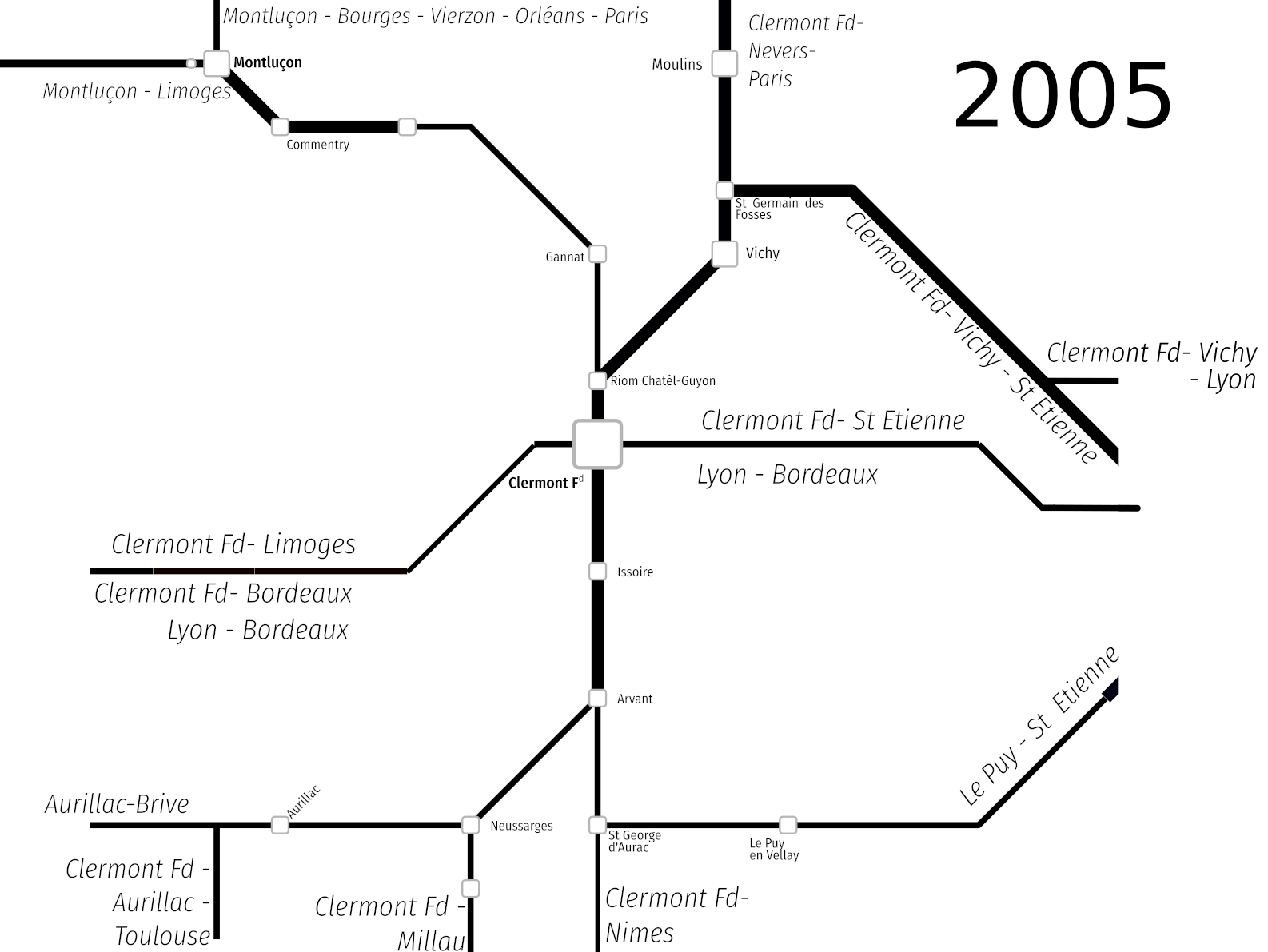

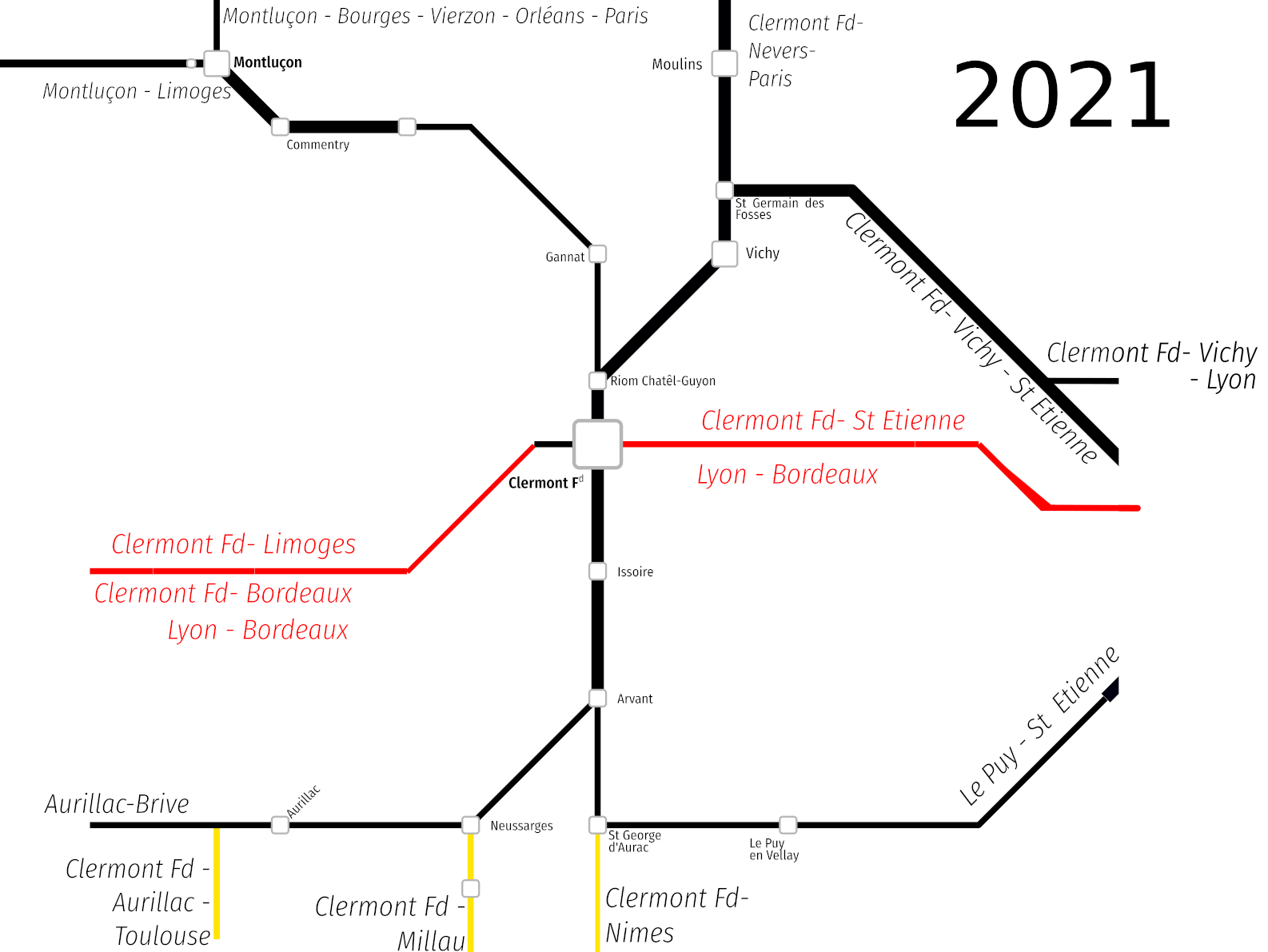

Since 1990, the French Rail network has shrunk by 13%, a figure that doesn’t sound too shocking until you realise that this means over 4252km of track has vanished in just under 30 years. What remains, with the exception of high-speed lines the two remaining major intercity axes (Paris - Clermont-Fd and Paris - Orléans - Limoges - Toulouse), is a network plagued by performance issues.

As a result, France’s regional passenger services experience low ridership while freight traffic struggles to find pathways through the sparse and highly congested remaining axes, resulting in high costs for track access and a significantly lower than average freight use.

It is clear that if we want to improve regional rail, improving the infrastructure will be at the heart of solving the problem, but how did France’s rail network end up in this state, and why have efforts to prevent further closures failed?

Under-investment, poor performance and closures

One of the key challenges for regional rail over the past 50 years has been the decline of network performance and reach. The rapid popularisation of the car meant numerous regional lines became uncompetitive. The French Government’s answer to this was to ignore regional rail and instead focus on the development of a TGV network capable of competing with the car over long distances.

The high cost of high speed lines meant that maintenance of regional lines was deferred in favour of speed reductions and service cuts, further reducing the attractiveness of regional rail. This resulted in further drops in ridership, which in turn justified the closure of some lines, and accidents such as the Brétigny disaster. Other lines, which survived these closures, were suspended due to safety concerns brought on by lack of maintenance.

By 2015, many small regional lines had already closed, leaving vast areas of many regions with no rail services. The closures also resulted in some regions being totally disconnected from one-another, leaving passengers with few options but to drive.

Since then, there has been a collective realisation that regional rail is important, and initial steps have been taken to halt the disappearance of lines. However the current policy is flawed in that it won’t undo the damage that has already been done, won’t make the network more attractive, and it won’t provide long term stability,

Doing the bare minimum: France’s current maintenance policy

Pérenniser is French for “perpetuate”, it is also the name of the policy undertaken by regions, SNCF Réseau (the Infrastructure Managers) and the French Government with regards to line maintenance.

The policy consists in taking actions to ensure the line does not close, however these actions frequently only do the bare minimum, replacing only the very worst segments of lines, and reducing speeds pending further works which have often not yet secured funding. This leads to situations where the speed limit is reduced following works, so as “not to further damage the parts of the track that have not yet seen maintenance”. This leads to situations where the operating speed of trains is often lower than the speed of cars, meaning regional rail is even less competitive.

Trains to nowhere? France’s rural branch lines

These policies have hit the most rural communities hardest: over the past 40 years, and particularly in the last 20 years, many rural lines have been suspended, while numerous others have been declassified entirely. These lines previously served rural communities, allowing for commutes into the city, as well as independent travel for the young and elderly.

Many of these tracks have since had their rails removed and have been converted into cycling or walking paths. While this practice does preserve the rail platform and give areas a new lease of life, it deprives rural areas of what could be vital transport links, as well as means of microfret delivery.

A lack of clear financial responsibility and long-term planning

All of these issues are ultimately symptoms of a common issue: lack of costed plan for maintenance and expansion. At present, SNCF Réseau continue to do basic maintenance on the whole network, however when major works are required, the funding often isn’t there, which leaves performance on lines dropping while SNCF Réseau, Regional, and Central governments haggle out an agreement on who pays and how much.

This issue was exasperated by the fusion of regions, which merged regions which often had significant budgetary, economic and demographic differences. The result is that some areas fail to gain funding for the rail networks in their area, as the new regions favour areas with highly developed existing networks.

Another issue this brings is that municipalities which currently have unused, closed or “temporarily closed” railways have no idea if or when those railways will ever be reopened. As a result of this, many have decided to convert these railways into cycling paths or pedestrian trails. This makes it even harder to bring such railways back into service at a later date.

Conclusion

The advent of the TGV, as well as years of neglect and administrative issues have resulted in a significant degradation of French Regional Networks. The next article will discuss the operational issues with passenger services, before a final article sets out how we can solve these issues.

This Article is the third of a series on fixing France’s regional trains. You can find out more in the introductory article, here.